Florence in 1507 was gripped by a cultural flourishing that few cities before or since have ever seen and dominated by two geniuses who detested each other: Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Leonardo was at his peak, urbane, handsome and gifted with phenomenal ability at seemingly anything he turned his hand to. However, his tendencies to procrastinate and over-experiment led to an output of just fifteen extant paintings from his sixty-seven years. Michelangelo was a generation younger, belligerent, unwashed, with a mono-maniacal focus on the human body and a personality so intense it struck terror into those he dealt with.

Note the way the figures are arranged into a series of pyramids from the bottom right corner. Raphael would use this pyramidal composition in his breakthrough painting.

In order to learn the secrets of human anatomy both had dissected corpses — Leonardo by invitation, Michelangelo by breaking and entering a morgue at night at massive personal risk. Both had used this to expand the limits of possibility of art: Leonardo through his attempts to represent the emotions of the soul through facial expressions and gestures; Michelangelo through his depiction of the tension and energy of movement.

This painting shows the serpentine posture that Raphael would reference in his breakthrough painting.

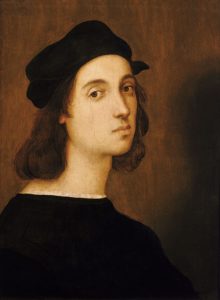

Also in Florence in 1507 was a twenty-four year-old from Urbino named Raphael. In the three years since he had arrived in Florence Raphael had spent countless hours copying motifs from both artists and absorbing their styles, but had struggled to gain commissions in the unprecedentedly fierce competition of Florence, and apparently led a peripatetic life picking up commissions in smaller towns whilst trying to ‘make it’ in Florence. However, a vicious feud between two families Perugia that had led to murder back in 1500 was about to give Raphael his big break.

The grieving mother of the slain youth who had died in her arms was determined to commemorate and venerate his short life through the creation of an altarpiece depicting the moment when the dead body of Christ was carried in his loved ones’ arms. Raphael was given the commission in 1505 or 1506, having not only developed a local reputation in his previous location of Perugia but also done an altarpiece for the other of the two warring families. At last was an opportunity to paint the kind of narrative story that Leon Battista Alberti had declared the highest form of painting.

Even more enticing was the prospect of depicting many different facial expressions of grief and multiple different depictions of the human body under strain. In short, this commission raised the tantalising prospect that he could put into practice what he had learnt from Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Raphael threw himself into the work, producing an unusually large number of preparatory sketches as he tried to do justice to the opportunity he had been given. In the one or two years between his commission and his completion his painting style transformed. Before he had been, for the most part, a painter of tranquil, balanced and beautifully detailed scenes that lacked any sense of motion, and of small groups of people in their own isolated little worlds.

Take, for example, his ‘Ansidei Madonna’ of 1505: John the Baptist is rather vacantly staring into space in a rather different direction to where he is feebly pointing; the bishop is engrossed in his book; and the Madonna and child are completely ignoring the extraordinarily-dressed visitors in their room.

His ‘Madonna del Baldacchino’, probably begun in 1506, shows some progression in that the figures all show some attempt to communicate to their companion or the other pairs in the picture, but the impression is a very static one of pairs being placed where they are simply to balance each other, like weights on scales.

Let’s turn now to the altarpiece that would make his name, the ‘Deposition of Christ’.

We are immediately struck by the sheer complexity of the scene, the sense of ‘suspended animation’ as if the figures have been frozen in the middle of motion, and the intense way the figures relate to each other. Raphael has leapt to another level — and he knows it. Look at the way the seated woman on the right imitates Michelangelo’s Doni Tondo, or the multiple pyramidal compositions on the left that endeavour to be more complex than that of the master of such compositions, Leonardo.

Florence’s cultural elite was riven between Leonardo the urbane, ineffectual dreamer and Michelangelo the stinking, belligerent monster; with this painting Raphael — young, handsome and serene, with good manners and a phenomenal workrate — became a worthy competitor in terms of talent, and a dream come true in terms of temperament. He was lionised by Florentine society, and within months had been summoned to Rome by the Pope to begin perhaps the most astonishingly productive twelve years of any artist’s life.

But back to the painting. What was it about the painting that gave it its sense of connection between its figures? After all, they are all looking in different directions, and some just into space. What gives this collection of paint daubed onto canvas its impression of weight and of bodies struggling to cope with it? And what gives it the sense of motion that his earlier pictures were so conspicuously lacking? A subsequent article will attempt to explain all of that, and attempt to reverse-engineer many of the compositional decisions Raphael took.