The London-based author Alain de Botton has released an engaging 14-minute video on his thoughts on what makes a city attractive. The honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects proposes six key qualities that attractive cities possess, namely

* A balance between consistency and variety

* People’s activities being on display

* Compactness of cities and of public spaces

* A balance of features that make it easy to orient oneself on the one hand, and mysterious enough to permit enjoyable exploration on the other

* A limit on all but buildings of exceptional civic value to five-storeys high

* The use of locally-sourced materials and architectural styles that reflect local ways of life.

De Botton says that these six qualities define a beautiful city, and that we know beauty when we see it — it’s reflected in the statistics for where people choose to go sight-seeing. However, we’ve succumbed to an intellectual confusion about what beauty is, and a sense that we are powerless to change things. As a result, greedy developers have free rein to build ugly but profitable buildings that make us feel alienated. De Botton concludes with a rousing call for the citizenry to work with government to produce developments that conform to his six principles and are therefore beautiful.

I recommend watching it, and I’ll assume that readers of this post have done so.

The purpose of this post is not to expose the contradictions in his post, although contradictions there perhaps are. To take the most problematic example, on the one hand he declares that we all have a good understanding of what beautiful cities look like (just examine the tourism statistics!); on the other he seems to assert that we are lumbered with a kind of ‘false consciousness’ about cities, particularly as regards privacy. (To de Botton, the ability of some people in Cartagena to peer into their neighbours’ homes at will represents some kind of ideal. Surely even if it is an ideal it is one that is highly dependent on the character of the neighbour.)

Instead, the point is to firstly critique a couple of his more specific recommendations; secondly to argue that his belief that no-one has built anything conforming to his six principles in decades could not be more wrong; and thirdly to argue that his recommendations may simply exacerbate the main problem he complains about.

Piazza Design

De Botton claims that a decent piazza has not been built anywhere on the planet in decades; despite this, he asserts, piazza design “isn’t rocket science”. Having thus summarily dismissed the intelligence and sensitivity of countless architects, urban designers, urban planners, politicians, developers and many lay experts, the Good Professor then expounds: there is apparently only one criterion for the design of a good square, that it should be neither too large nor too small. Anything larger than 30m across starts to become so large as to produce alienation. This is because beyond that we lack the ability to hail someone on the other side of the square. I guess de Botton is doing some armchair extrapolation based upon the acuity of the human eye and the reach of the voice here, rather than measuring the dimensions of beloved piazzas. For example, all of the following are, ex hypothesi, unattractive piazzas:

Saint Mark’s Piazza, Venice: 171m by 70m

Saint Mark’s Piazetta, Venice: 88m by 48m

Saint Peter’s Piazza, Vatican City: 240 by 210m

Piazza Navona, Rome: 257m by 55m

Piazza del Campo, Siena: 120m by 100m (this is, of course, demonstrably large enough to race horses around)

Michelangelo’s Campidoglio, Rome: 80m by 50m

The massively influential connoisseur of medieval piazzas, Camillo Sitte, found that the average dimensions of the squares he considered great were 142m by 58m.

Now, piazzas may be valued for many different reasons, and de Botton is perfectly at liberty to argue that these piazzas are bad public spaces and seek to persuade us. (“Do try to understand my lessons, Michelangelo: this isn’t rocket science!”) However, if he does this then he must surely ‘bite the bullet’ and no longer rely on tourism statistics to demonstrate our knowledge of what makes an attractive city — does any tourist to Rome, Venice, or Siena not prioritise seeing these piazzas?

Consistency and Variety

Secondly, de Botton praises a street in Amsterdam where each building is restricted to the same height and width, and the colour range is restricted. Aside from these restrictions, the designers have been given free rein. This is a recipe for a beautiful street, in de Botton’s estimation; not in mine.

The flaw in the recipe for beauty can perhaps best be seen by analogy. Imagine if we were to measure the height and other vital statistics of a huge range of fashion models, and use this data to determine the averages. If he were a modelling agent, de Botton would perhaps hire a group of models who all have these vital statistics but whose faces may express every kind of individuality known to humanity. The result would surely not necessarily be beautiful, and could be pretty disastrous for the modelling campaign. In other words, the features of the face (or facade, if you will) are clearly a crucial aspect of beauty, and to leave this to the whim of individual design teams doesn’t seem any more likely to lead to beauty than the developer free-for-all that de Botton seems to think is the status quo.

Height Limits

Thirdly, de Botton claims that building heights should not, except for buildings of extraordinary civic importance, exceed five storeys. Anything more, he asserts, makes us feel small and insignificant.

This is surely wrong in at least two respects. Firstly, the apparent size of any building is entirely dependent on the observer’s position. (Many urban experts seem to be oddly forgetful on the small but crucial point when drawing up criteria for judging urban space.)

Secondly, this assumes that we compare our physical size to those of buildings; however if we do this then almost any structure designed for human use will make us feel small. A bungalow or even a garden shed is comfortably larger than I am; the average room, if I can make myself adopt the requisite mindset, must appear as a gaping void. If tall buildings really do make us feel insignificant then surely the rule should be to build structures that are as small as feasible. Why, then, does de Botton feel such a strong attraction to these mid-rise blocks?

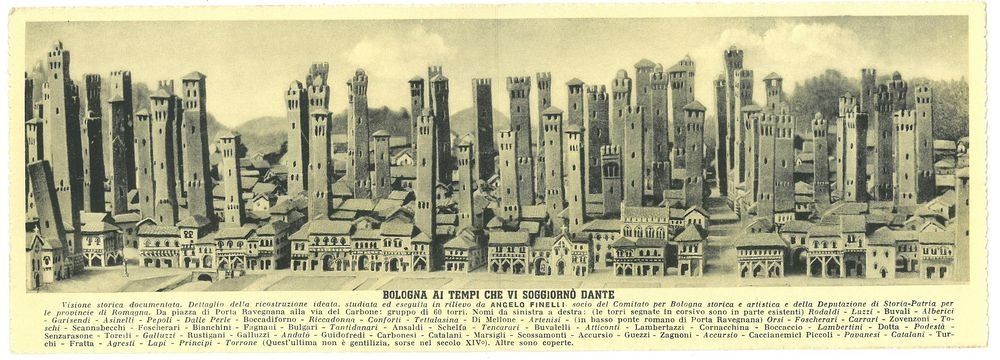

I can only think that these five-storey blocks have the comforting imprimatur of tradition. The old cores of many cities are fairly commonly built up to about five storeys but not many more. This was not due to some kind of technical limitation on building high: look at, for example, the forest of skyscrapers in medieval Bologna…

… or the towers of San Gimignano. In the Middle Ages the wealthy ‘hijacked the skies’ and engaged in an aggressive status race to build the town’s tallest tower. Now we book trips to see these UNESCO-recognised towers. It’s a funny old world, Alain…

Yet it was surely not aesthetic considerations that made mid-rise buildings the norm in many old areas, but economics. They are the result of a trade-off between the convenience of spatial proximity to a city centre and the inconvenience of walking up so many flights of stairs. Beyond a certain number of storeys it becomes more convenient to live slightly further from the city centre in a lower storey. Encouraged by the combination of the undesirability of higher-storey flats and the additional costs and complexities of taller buildings, in many cities the result was a four-to-six storey standard fanning out along the most convenient routes. Supporting evidence includes the design of the ‘Haussmann buildings’ of Paris, which have five storeys plus a garret in the mansard roof. The lowest residential floor the ‘piano nobile’) is the most opulent; the garret is proverbially the lodgings of starving artists.

The only way a building of eight storeys can make us feel more insignificant than a building of five storeys is, I suggest, if we imagine ourselves having to clamber up to the top and believe that it will tire us out. After the invention of the lift this no longer applies. There are, of course, other reasons why taller buildings may not be favoured, for example depending on the design they may block too much sunlight or cause significant downdraughts. However, de Botton’s favoured reason seems far from compelling.

Bottoning Out

De Botton believes that modern cities are simply not built according to his criteria. Surely this could not be further from the truth. One of the most ubiquitous types of development since the War very often conforms to all of de Botton’s criteria: the shopping mall.

Consistency & Variety

Typically the shopping mall combines consistency and variety in a way reminiscent of de Botton’s Amsterdam street: each shop is exactly the same height and often the same width; the contents of each shop may have little relation to the others and each express their individual characters (or ‘brands’), but the fittings of the corridors immediately outside and connecting the shops have a rigorous uniformity.

Activity

There is plenty of activity on display, from the milling crowds to the shop assistants going about their jobs, from people giving out free samples to people putting on a show. De Botton complains that much office activity is hidden in anonymous towers and that we have little idea of the fascinating projects going on within. But such projects very often involve doing specialist work on a computer that we would not understand even if we could see; it is easily understandable retail shops in places like malls that quite closely approximate de Botton’s apparent dreams of a ‘butcher, baker, candlestick-maker’-type high street.

Compactness

The shopping mall is relatively compact given that there may be more shops in a mall than in many districts of a city put together, and the corridors are often narrow so that the shopper can get a good view of the goodies for sale on both sides of the corridor. A food court offers many of the functions of a compact piazza, and all of the ones de Botton celebrates.

Most often the shopping mall, unless constrained by a lack of land, restricts itself to being midrise and stretches out along corridors instead of upwards. In a high-rise mall a lift shoppers must typically use lifts, thus bypassing many floors and many shops; where the mall is mid-rise shoppers can be encouraged to rely on escalators instead. By putting the escalator that connects a floor to the lower one some distance from the escalator that connects the floor to the upper one, the shopper is strongly encouraged to walk past many different shops and therefore many temptations.

Orientation & Mystery

On the one hand the typical shopping mall is designed to be easy to orient yourself, with corridors leading to large ‘anchor’ shops and different zones of the same mall sometimes being given different characters, or themes. On the other hand, shopping malls are notorious for introducing disorienting aspects into their design. Cues about the time of day and the cardinal directions are often removed by providing consistent lighting and an absence of clocks; different floors in the same zone are typically stylistically near-identical, strongly encouraging the shopper to use shops as wayfaring aids. This both boosts brand recognition and increases sensitivity to new arrivals.

Distinctiveness

Lastly, the shopping mall very often tries to provide some kind of distinctive experience that makes it unique. Mall developers, like de Botton, don’t want people travelling long distances to see a place that’s merely samey. Irrespective of whatever manipulation may be going on, many shopping malls do, or did, support some of the local culture of a place. Particularly at their peak in the 80s and 90s, people used to spend much of their free time socialising, flirting, dating, exercising, and experimenting with their lifestyle and image. In many places they are, or were, the social hubs of the area, and what both happened at the mall and was provided by the mall reflected local culture to some degree.

Developments that conform to de Botton’s criteria are everywhere; and yet I do not believe that he is proposing raising a citizen army to fight for more malls. De Botton seems to assume that by restricting developers to a mid-rise level we would therefore be frustrating the ‘greed of property developers’; and yet, as we saw in the example of the typically mid-rise mall, this might actually be to the developer’s advantage. For a given Gross Floor Area it is often better to have a larger building footprint than a smaller one, for example because of the extra footfall if the property happens to be on a useful route.

A neighbourhood might be developed according to strict Bottonian principles, and yet all the streets and buildings might be privately held by the same developer. Because the land has been privatised the owner may hire private security forces to patrol it and may have the right to limit certain types of activity occurring on his streets and piazzas (such as the political protest de Botton advocates), or to clear away ‘undesirable people’. This is hardly a hypothetical scenario, and it is one that seems far more objectionable than someone building a six-storey building.

Quite simply, de Botton’s medicine may only exacerbate the disease.

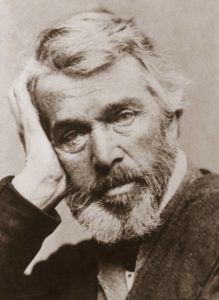

An Urbanist Carlyle?

De Botton strikes me as being a kind of agreeably mild Thomas Carlyle. The great Victorian thinker surveyed the spiritual confusion and consequent paralysis of his age and concluded that the latter was far worse than the former. He therefore urged that people suffering from these problems throw themselves into work so that there is no time to ponder philosophical conflicts. “Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do that with all thy might and leave the issues calmly to God”, he famously counselled. The Victorian age was awash with similar sentiments, from ‘the devil will make work for idle hands to do’ to Rudyard Kipling’s infamous description of leisure time as ‘the unforgiving minute‘. I recommend Houghton’s superb book ‘The Victorian Frame of Mind.’ However, the boost these attitudes gave to the pre-existing Protestant Work Ethic probably helped the development of capitalism; and yet it was capitalism, for all its virtues, that was busy shredding established patterns of life and therefore exacerbating the sense of dislocation and spiritual confusion that was a root of the paralysis.

In a similar way, de Botton surveys the aesthetic confusion and helpless paralysis of his age and seems to conclude that the latter is the worse problem. He therefore declares that the millennia-long debate about aesthetics is merely intellectual confusion and that we should throw ourselves into the politics of urban development. Since his principles are entirely compatible with maximising developer profits, his followers may only be exacerbating the greed and inequalities whose urban manifestations seem to be at the root of de Botton’s dissatisfaction.

Also like Carlyle, de Botton blithely ignores the obvious concern that different parts of society may have different, and even antagonistic interests. Carlyle’s gospel of work became increasingly implausible in tandem with the development of class conflicts about the control of the workplace and the monetary proceeds of the work. In Carlyle’s defence, he was writing before the development of working-class organisation and the rise of socialism; I’m not sure de Botton has that defence. “Collectively, we’ve got enough money” to create beautiful cities, de Botton sighs. Quite so, for we are far wealthier than any previous society. But the point is that this money is not in some collective pot awaiting more judicious collective decisions but is distributed with staggering inequality. It is disproportionately in the hands of the ‘pizza corporations and hedge funds’ he lambasts, and I do believe he knows it.

He knows it, just like the author of a book on ‘the pleasures and sorrows of work’ knows that his celebration of shop-workers taking pride in what they do and happy to show it is starry-eyed in a world where many shop-workers are on insecure contracts, low pay and work in alienating working conditions. Just like the author of a book on the varieties of love knows that it is profoundly difficult to reduce beauty to a six-faceted formula.

De Botton feels alienated by modern cities; I dare say he’s far from alone. But the solution is not to retreat into mere formalism that ignores the substantive problems and as a consequence may exacerbate them. Any resolution to the problems de Botton raises surely must involve squarely facing up to the root causes of any alienation, and by looking with greater attention at the many lessons that beautiful cities across the world can teach us.